High Output Management - by Andrew Grove

ISBN: 978-0679762881

READ: Jan 27, 2015

ENJOYABLE: 8/10

INSIGHTFUL: 9/10

ACTIONABLE: 9/10

Critical Summary

High Output Management provides a comprehensive overview of a managers role and purpose. The book focuses around a central thesis that a manager's objective is to increase the output of the work of those below and around him. A manager should therefore choose high-leverage activities that have a multiplicative impact on the overall output of his subordinates and peers. For example, providing clear direction to a team may only require a small amount of the manager's time, but yields tremendous value in terms of the output of the team.

This book is great for both new and experienced managers since it provides valuable frameworks and strategies for all kinds of common managerial tasks. Below are the core topics covered in this book:

- Delegation - In order to maximize leverage, a manager needs an optimal number of subordinates to whom he can delegate to. Successful delegation provides lots of leverage, whereas poor delegation ends up netting no leverage since it turns into errors and micro-management.

- Meetings - Meetings are extraordinarily expensive to a company. There are three types of recurring meetings: one-on-one's, staff meetings, and operational reviews. Each of these meetings should have a clear framework for maximizing value and minimizing time-waste. There are also one-off meetings centered around making a particular decision – such meetings should be especially carefully planned and executed since they are often scheduled ad-hoc without a clear purpose and with too many participants.

- Making decisions - When making decisions, there's a fragile power dynamic that needs to be carefully handled. Managers should facilitate free and open discussion amongst all parties until a consensus emerges. In cases where a consensus does not emerge naturally, the manager should push for a decision.

- Dual reporting - Dual reporting is inevitable in most large organizations. Consider advertising: should each division of a company decide and pursue its own advertising campaign, or should all of it be handled through a single corporate entity? The optimum solution calls for the use of dual reporting where each division controls most of their own advertising messages but a coordinating body of peers consisting of the various divisional marketing managers chooses the advertising agency and creative direction.

- Motivating employees - Our society respects someone's throwing himself into sports, but anybody who works very long hours is regarded as sick or a workaholic. Imagine how productive our country would become if managers could endow all work with the characteristics of competitive sports? Eliciting peak performance means going up against something or somebody, and turning the workplace into a playing field where subordinates become athletes dedicated to performing at the limit of their capabilities.

- Performance reviews - Performance reviews are easily mistaken as simply a way to assess performance and evaluate compensation. The fundamental goal of a performance review is to improve the subordinates performance. A review will influence a subordinate's performance for a long time, which makes the activity one of the manager's highest-leverage activities. Thus great care needs to be taken in the preparation and delivery of a performance review.

Production

Design production flows around limiting steps–the most expensive or time-consuming parts of the process.

Choosing Performance Indicators

Indicators pull your attention to them. To avoid overreacting to any single indicator, you should pair indicators. eg. test coverage and user bug incidents, inventory levels and incidence of shortages

Effectively designed indicators should:

- measure output, not activity (eg. # of cars sold vs # of phone calls made)

- measure a physical, countable thing

- pair output with a measurement of quality (eg. # of issues found in an audit, customer complaint log, objective/subjective rating, etc.)

Such indicators:

- spell out very clearly what the objectives of an individual or group are

- provide a degree of objectivity when measuring an administrative function

- give us a measure by which various groups performing the same function can be compared with each other

Leading indicators

Leading indicators show you in advance what the future might look like and gives you time to take corrective action.

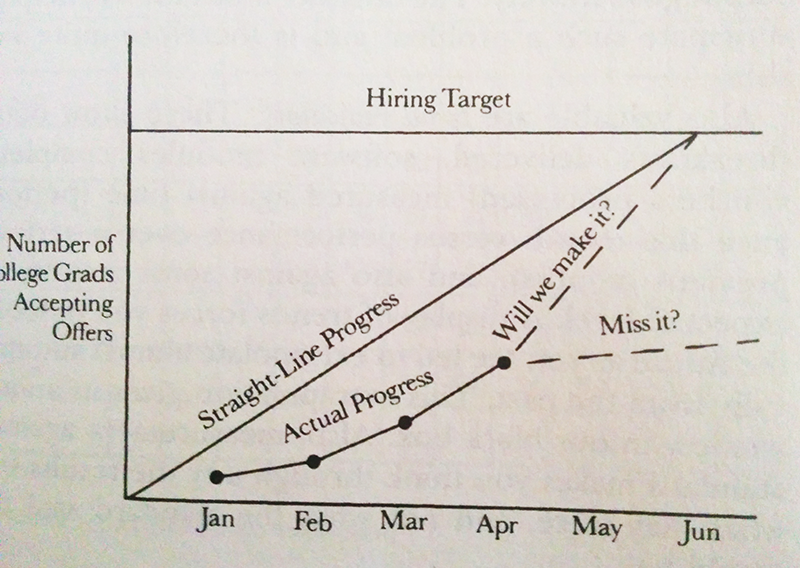

linearity indicator: plots a linear line of output needed to reach a target, versus actual output

Trend Indicators

Trend indicators show output against time and some standard expected level. Makes you ask why?

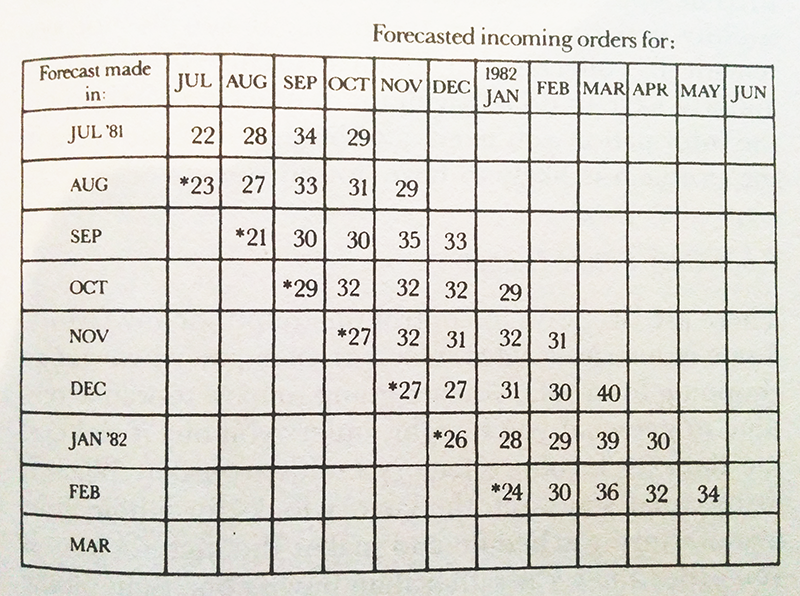

stagger charts: records outlook, how outlook has varied, and actual output. By repeatedly observing the variance of one forecast from another, you improve your ability to forecast–thus improvement or deterioration of the forecast becomes a powerful indicator.

Building to forecast

Build to order = building when the need arises.

Build to forecast = risk capital to be able to respond to a future anticipated need, eg. hiring before a specific need develops

Assuring quality

To get acceptable quality at the lowest cost, you should reject defective material at a stage where its accumulated value is at the lowest possible level.

Three common types of inspections, using engineering production as an example:

- receiving inspection (eg. reviewing specs/scoping for a feature to make sure they are comprehensive and acceptable to the customer)

- in-process inspections (eg. code reviews)

- final inspection (eg. qa team)

Management

manager's output = output of his organization + output of neighboring organizations which benefit from his know-how

A manager should keep many balls in the air at the same time and shift his energy and attention to activities that will produce the greatest output.

Four key managerial activities:

- Information-gathering is the basis of all other managerial work. All other activities are governed by the base of information that you have about the tasks, issues, needs, and problems facing your organization. The information most useful to managers comes from quick, often casual verbal exchanges by visiting different parts of the company.

- Decision-making

- Nudging – Imparting a sense of the preferred method of handling something, eg. making a phone call to an associate suggesting that a decision being made in a certain way, sending a memo that shows how you see a particular situation

- Being a role model – Conveying values and principles by doing and doing visibly.

Increasing managerial output

Managerial productivity can be increased in three ways:

- Increasing the rate in which you perform activities

- Increasing the leverage associated with the activities you perform

- Shifting your activities from low-leverage to high-leverage

High-leverage activities:

- When many people are affected by one manager eg. company roadmap/budget planning.

- When a person's activity over a long time is affected by a manager's brief, well-focused set of words or actions eg. retaining a key employee, performance review, training.

- When a large group's work is affected by an individual supplying a unique, key piece of knowledge or know-how.

Avoid managerial meddling – assuming command of a situation rather than letting the subordinate work things through himself.

Delegation = leverage

Delegation only works when both parties share common information and a common set of operational ideas or notions on how to go about solving problems. Otherwise, the delegates is only effective with specific instructions, which produces an environment of slow managerial leverage.

Delegation without follow-through is abandonment. Even after you delegate something, you are responsible for its accomplishment.

Monitoring is not meddling. Monitoring the results of delegation resembles the monitoring used in quality assurance – we should monitor at the lowest-added-value stage of the process, and use some form of variable frequency and sampling. Monitor decision- making process by asking delegatee specific questions and seeing if he answers them convincingly.

How many subordinates should you have?

If you don't have enough, your leverage is reduced. If you have too many, you get bogged down (and your leverage is reduced).

Rule of thumb: a manager whose work is largely supervisory should have six to eight subordinates. This allows for a half-day per week to each subordinate. Deduct one for every accountability in which a manager provides know-how to another group.

Managerial Productivity

Interruptions are the plague of managerial work. Strive toward regularity. Do everything you can to prevent little stops and starts in our day.

To prevent others from interrupting you, have regularly scheduled meetings so that issues and questions can be accumulated then batch processed.

Meetings

meetings = the medium through which managerial work is performed (eg. decisions, sharing of know-how, and nudging)

process-oriented meetings

process-oriented meetings = recurring meetings for knowledge and information sharing; pre-determined meeting process and objectives

Always use a "hold" file for pre-planning and batching agenda items for the next meeting. Always take notes and share the recap.

My google doc meeting system accomplishes this.

1:1's - Meeting between manager and a subordinate for mentoring and knowledge sharing. Manager should listen, ask lots of questions to get to root of problems, and coach. Make it a heart-to-heart; drop the water line. Frequency of 1:1's depends on subordinate's experience. Leverage = 90 minutes of your time can enhance the quality of a subordinates work for two weeks, increase your understanding of their work, and create a common base of knowledge for effective delegation. 1:1's are also a great parenting technique.

Staff Meetings - Should only be used for discussing anything that affects more than two of the people present–otherwise, the manager should ask them to break it off and continue their exchange later. The manager's most important role is to facilitate the meeting and control its pace and thrust so it stays on track. Managers should leave the work of working out issues to subordinates, and help reach decisions. Opposing views and confrontation that develops gives you a much better understanding of an issue.

Operation Reviews - Medium of interaction for people who otherwise don't have opportunities to work or meet with one other.

The format should include formal presentations in which managers describe their work to other managers who are not their supervisors, and to peers in other parts of the company. Keeps teaching and learning going on between employees across the organization who don't have 1:1s or staff meetings with each other. Important for both junior and senior managers: junior person benefits from the comments, criticism, and suggestions of the senior manager, who in turn will get a different feel for problems from people familiar with their details.

The meeting should be organized and conducted by the supervisor of the presenting managers and help them decide what issues should be talked about, what should be emphasized, and what level of detail to go into. Reviewing manager should ask questions, make comments, and impart a spirit to the meeting that provokes audience participation and encourages free expression by his example–he is a role model. Audience should ask questions and make comments.

If I were to organize a meeting like this at Dev Bootcamp, I would contain the meeting intentionally to force presenters to pick the most important things. eg. "You have 4 minutes – Tell us your Q1 goals and remind us how they relate to DBC's mission. Tell us what you're working on–and why (relating it back to NTG's)–and tell us what the upcoming milestones are of that project(s) and when you expect to reach those milestones."

mission-oriented meetings

mission-oriented meeting = ad-hoc meeting designed for a specific output or decision

Before initiating a meeting, make sure you know what you are trying to accomplish and whether the meeting is necessary, desirable, or justifiable. If you're an invited participant, ask yourself if the meeting and your attendance is desirable or justified.

Eight people should be the absolute cutoff for a meeting called to make a decision. Decision-making is not a spectator sport.

Organizer should send out an agenda that clearly states purpose of the meeting, as well as what role everybody there is expected to play to get the desired output. Meeting notes from discussion, decisions made, and specific action items should be sent out as soon as possible, before attendees forget what happened.

If the meeting was worth calling in the first place, the work needed to produce the minutes is a small additional investment (high leverage) to ensure that the full benefit is obtained from what was done.

I am already in the habit of sending out agendas, but it'd be great to also start pre-stating the role of everybody's participation.

If people are spending more than 25% of their time in ad hoc mission-oriented meetings, it is a sign of malorganization.

Meetings are expensive–the dollar cost of a ten-person meeting could be $2,000. Most expenditures of $2,000 have to be approved in advance by senior people, yet a manager can call a meeting and commit $2,000 on a whim. Wasting time in a meeting = wasting the company's money.

Making Decisions

Managers' technical knowledge inevitably become dated over time, so decision-making in a technical, information-driven environment needs to be a process that takes into the account both people with knowledge-power and people with position-power.

Ideal decision-making process:

- Free discussion

- Clear Decision

- Full Support (support != agreement)

^ Repeat free discussion if full support isn't reached.

Peer-group syndrome

When everyone at the discussion table is an organizational equal, the discussion can end up going in circles because none wants to go against the group.

Peers tend to look for a more senior manager, even if he is not the most competent or knowledgeable person involved, to take over and shape a meeting. The peer-plus-one approach deliberately brings in a senior manager after free discussion to help do so.

Other paralyzing phenomena: fear of sounding dumb (affects both people in a power of knowledge and position), and fear of being overruled.

Making the decision

If no consensus has emerged after free discussion wherein all points of view, facts, opinions, and judgement were aired without position-power prejudice, then and only then should the senior manager make a decision. It is destructive for him to wield that authority any earlier, since this cuts off the full benefit of open discussion.

Don't push for a decision prematurely–in fact it's probably best to not even offer an opinion. Ask questions and frame issues to make sure you have heard and considered the real issues rather than the superficial comments that often dominate the early part of a meeting. But if you feel that you have already heard everything, that all sides of the issue have been raised, it is time to push for a consensus–and failing that, to step in and make a decision.

Framing decisions that need to be made

A manager should settle six key questions in advance:

- What decision needs to be made?

- When does it have to be made?

- Who will decide?

- Who will need to be consulted prior to making the decision?

- Who will ratify or veto the decision?

- Who will need to be informed of the decision?

Planning

How to plan:

- Establish projected needs. Don't get trapped into only focusing on today's problems. Ask what are the needs today? What will they be a year from now?

- Establish present status and course–list present capabilities and projects you have in the works

- Compare and reconcile steps 1 and 2 to close the gap. Ask: what do I need to close the gap? What can I do to close the gap?

The output of planning is decisions made and actions take as a result.

This is similar to Peter Drucker's paper "What Does a Leader Do?", where he says that a leader should (1) ask what needs to be done and what is best for the company, (2) develop action plans.

Remember that each time you say "yes" to something, you are implicitly saying "no" to something else.

Management by Objectives

MBO system answers two questions:

- Where do I want to go? The objective.

- What are the steps to getting there, and when should they occur so that I know I am getting there as planned? Key milestones and results.

Objectives and milestones are set and tracked quarterly or monthly.

MBO system provides focus–the number of objectives should be limited.

The hierarchy of objectives in an organization should be aligned with one another. eg. a managers objective aligns with that of his superior's objective

Hybrid Organizations

All large organizations are hybrids of two extreme forms–totally mission-oriented (decentralized) or totally functional (centralized)–and often pragmatically shift between the two.

For example: Intel consists of mission-oriented business divisions (eg. Components, Microcomputers, Systems) and various functional groups where 2/3s of their employees work (eg. sales, finance, legal).

Dev Bootcamp's mission-oriented groups are Prep, Teachers and Careers (they deliver our core services of instruction and job placement). Engineering is our main functional group.

Functional groups can achieve economies of scale and have their resources shifted or reallocated to respond to changes in corporate-wide priorities without too much hassle. In addition, the know-how of functional groups can be applied to the entire organization, giving their knowledge and work enormous leverage.

The disadvantage of functional units is the information overload hitting a functional group when it must respond to the demands made on it by diverse and numerous business units. Even conveying needs and demands often becomes very difficult–a business unit has to go through a number of management layers to influence decision-making in a functional group. This is evident in the negotiations that go on to secure a portion of centralized–and limited–resources of the corporation, be it production capacity or space in a shared building. Indeed, things often move beyond negotiation to intense and open competition among business units for the resources controlled by the functional groups.

This manifested itself at Dev Bootcamp–there was heated competition for engineering budget amongst various circles.

There's only one advantage of organizing much of a company in a mission-oriented form: it allows individual units to stay in touch with the needs of their business or product areas and initiate changes rapidly when those needs change. That is it. All other considerations favor the functional type of organization. But the business of any business is to respond to the demands and needs of its environment, and the need to be responsive is so important that it always leads to much of any organization being grouped in mission-oriented units.

The most important task for the company as a whole is the optimum and timely allocation of its resources and the efficient resolution of conflicts arising over that allocation.

Theoretically, the allocation of shared resources and the reconciliation of conflicting needs and desires of independent units are the function of corporate management. Practically, however, the transaction laid is far too heavy to be handled in one place.

Dual Reporting

The need for dual reporting is unavoidable in hybrid organizations.

Example: who should a security manager at a manufacturing plant report to–the plant manager or the corporate director of security? The plant manager knows nothing about the technicalities of security, and the director works at corporate headquarters so he wouldn't know if the person even showed up or otherwise performed badly? The solution: dual reporting.

Functional organizations tend to silo groups like engineering from the divisions their serving, leaving them with no idea of what the customers want or what their objective is. While a mission-oriented organization may have clear objectives at all times, it suffers from inefficiency and poor overall performance due to fragmentation.

This helps frame challenges at Dev Bootcamp. Engineering used to be distributed, but now has become centralized. While the engineering team is now much more efficient, they don't have the immediacy and priorities coming from circles and end-users since they report to me, not circle leads. But this is natural: as cited earlier in the notes, the only advantage of organizing much of a company in a mission-oriented form is that it allows individual units to stay in touch with the needs of their business or product areas.

Dual reporting doesn't have to require an additional individual – it can also be a peer group. This requires the voluntary surrender of individual decision-making to the group.

For example, a group of manufacturing managers who's respective divisions are led by executives with a finance background realize they share common technical problems that their bosses can't help them with. So they form a committee that tackles issues common to all.

In essence, at Dev Bootcamp, we've shifted to a functional structure where engineering reports to me. This comes at the cost of engineers not staying in touch with the needs of the various areas of the business they are serving (and places the burden of gathering and translating that information into action on me). An alternative would've been to have engineers in each circle report to their circle leads as well as to a single technical lead (eg. an engineer in marketing/admissions, one in careers, and one in prep/teachers). Theoretically there wouldn't necessarily have had to a tech lead–the engineers in each circle meet as a peer group to identify and tackle issues common to all (the need to have a central place for core data such as students, curriculum, etc).

Learn more about Matrix Management

Example: advertising

Hybrid organizations need a way to coordinate the mission-oriented units and functional groups so that the resources of the latter and allocated and delivered to meet the needs of the former.

Consider advertising: should each business division decide and pursue its own advertising campaign, or should all of it be handled through a single corporate entity? Each division clearly understands its own strategy best, and therefore presumably best understands what its advertising message should be and to whom it should be aimed. This suggests advertising should stay in the hands of divisions. On the other hand, the products of various divisions often all serve the needs of a specific market, and taken together represent a much more complete solution to the customers' needs than what can be provided by an individual division. Here the customer and hence the company benefit if all the advertising stories are told in a coherent, coordinated fashion. Advertising sells not just a specific product but the entire company–ads should project a consistent image.

The optimum solution calls for the use of dual reporting.

The divisional marketing managers should control most of their own advertising messages. But a coordinating body of peers consisting of the various divisional marketing managers and perhaps chaired by the corporate merchandising manager should provide the necessary functional supervision for all involved. This body would choose the advertising agency, creative direction, and define the way divisions deal with the agency.

There are two questions that need to be asked to align everyone around a Marketing owning global alumni communications. (1) What functional purpose does "managing alumni" serve? (2) Should each circle pursue its own alumni management strategy? Or should it all be handled through a single entity? What are the tradeoffs?

Multiple planes

People can exist in multiple roles across different planes of an organization, eg. President and part of strategic planning group. Such groups can be transitory.

Motivating others and eliciting peak performance

The single most important task of a manager is to elicit peak performance from his subordinates.

No matter how well a team is put together, no matter how well it is directed, the team will perform only as well as the individuals on it.

We can improve performance through training and/or motivation.

When a person is not doing his job: he is either not capable or not motivated. To determine which, we can employ a simple mental test: if the person's life depended on doing the work, could he do it? If the answer is yes, that person is not motivated; if the answer is no, he is not capable.

A subordinate saying "I feel motivated" means nothing. What matters is if he performs better or worse because his environment changed.

Maslow's theory of motivation: needs cause people to have drives which result in motivation. To maintain a high degree of motivation, we must keep some needs unsatisfied at all times.

- Physiological - basic needs such as food and shelter

- Security - protection from losing basic needs (eg. medical insurance)

- Social/affiliation - inherent desire to belong to a common group; motivates us to join a company and show up for work

- Esteem/recognition - "keeping up with the Joneses" – the never ending ladder of upward achievement and recognition

- Self-actualization - the need to achieve one's personal best in a chosen endeavor; competence-driven = job or task mastery; achievement-driven = need to achieve in all that they do.

Peak performance and output will result when everyone strives for a level of achievement beyond their immediate grasp, even if they'll fail half the time. Goals should be focused on output – not just attaining knowledge or abstract answers.

Also: don't forget the SCARF model

Once in the self-actualization mode, a person needs measures to gauge his progress and achievement: eg. management by objectives, performance indicators and milestones, performance reviews.

How to systematically lead others to self-actualization

Our society respects someone's throwing himself into sports, but anybody who works very long hours is regarded as sick or a workaholic. Imagine how productive our country would become if managers could endow all work with the characteristics of competitive sports.

Eliciting peak performance means going up against something or somebody, and turning the workplace into a playing field where subordinates become athletes dedicated to performing at the limit of their capabilities.

A manager has to see the work as it is seen by the people who do that work every day and then create indicators and an arena of competition so that his subordinates can watch their "racetrack" take shape.

The manager should be a coach: take no credit for the success of his team (earns trust), be tough on the team, and understand the game well because he was a good player himself at one time.

Management style should vary dependent on task-relevant maturity

At Intel, when they rotated managers around to different groups, neither the managers nor the groups maintained the characteristic of being either high-producing or low-producing as the managers were switched around.

Thus, high output is associated with particular combinations of certain managers and certain groups of workers, and that a given managerial approach is not equally effective under all conditions.

The most effective management style depends on the maturity of subordinate(s) as it pertains to their current task. This theory parallels the development of the relationship between a parent and child.

Managers should adjust their management mode depending on the TRM of subordinates. TRM can change quickly–eg. when sudden change occurs and there is much more ambiguity and uncertainty.

- Low TRM = structured, task oriented management style: "what", "when", "how""

- Medium TRM = structure is self-provided; emphasis on two-way communication, support, mutual reasoning

- High TRM = involvement by manager minimal: establishing objectives and monitoring

Neither deciding the TRM of subordinates or having the discipline to aadjust your management style based on it is easy.

A lot of managers have the misperception that they are good delegators, when in fact a lot of their suggestions are recede by subordinates as orders.

As managers, raising the TRM of subordinates leads to higher managerial leverage (since the manager can delegate more tasks to the subordinate).

At Dev Bootcamp, instructing others to use a disciplined project management workflow was a high-leverage accomplishment because it allows me to delegate more tasks to our engineering time without as much oversight.

Performance reviews

Performance reviews are the single most important form of task-relevant feedback a supervisor can provide. Performance reviews should be part of managerial practice in organizations of any size and kind.

What is the fundamental purpose of a performance review? To improve the subordinate's performance.

A review will influence a subordinate's performance for a long time, which makes the activity one of the manager's highest-leverage activities.

Reviews focus of a review is on the skill level of the subordinate, to determine what skills are missing and to find ways to remedy that lack; and second, to intensify the subordinate's motivation in order to get him on a higher performance curve given his skill set.

Assessing performance

First, clarify in your own mind what it is you expect from a subordinate, and then attempt to judge whether he performed to expectations.

Take into account: - Output measures vs internal measures (delivering work and meeting sales quotas vs how we went about that work) - Long-term-oriented vs short-term-oriented performance (eg. completing features on schedule vs refactoring code) - Time offset between activity and output (eg. SEO changes) - For managers: manger, in addition to their group's output, consider how the manager is adding value - Focus on output, not potential – the performance of a manager cannot be higher than the one we would accord to his organization.

Decision to promote should be tied to performance. Promotions speak loudly to the organization if its values–by elevating someone, we are, in effect, creating role models for others in our organization. When we promote our best, we make it clear that performance is what counts.

Delivering assessments

Three L's:

- Level: be totally frank–credibility and integrity of the entire system depends on it. Be straightforward in praise as well as criticism.

- Listen: employ your entire arsenal of sensory capabilities to make certain your points are being properly interpreted by your subordinate's brain.

- Leave yourself out: performance review is about and for your subordinate. Keep your own insecurities, anxieties, and guilt out of it.

Don't deliver a ton of messages which will simply be forgotten. Target a few key areas that will improve performance. Do this by writing out everything on a sheet of paper then grouping and choosing three key areas... you'll often come up with conclusions that surprise you.

When communicating a major performance problem, be sure to go through all stages of problem-solving together with your subordinate: ignore, deny, blame others, assume responsibility, find solution. Any outcome that includes a commitment to action is acceptable, even if there isn't universal agreement about the problem.

Don't overlook star performers–since star performers account for a disproportionate share of work in an organization, if they get better the impact on the group is that much greater.

If you're going to give your subordinate a written review, do it sometime shortly before the face-to-face so they have time to react then come back to rationality.

See example of a written review on p. 200

Interviewing

Purpose of the interview:

- select a good performer

- educate him as to who you and the company are

- determine if a mutual match exists

- sell him on the job

The applicant should do 80 percent of the talking during the interview, and what what he talks about should be your main concern. Control the interview so as to not waste time (eg. tell the candidate to talk about a particular subject).

Four categories of questions:

- What are the candidates technical skills? (describe some projects, what are your weaknesses?)

- How did this person perform in an earlier job using his skills and technical knowledge? (past achievements, past failures)

- Discrepancies between what he knew and what he did (what you learn from failures? problems in current position?)

- Operational values (why should my company hire you? why should engineer be chosen for marketing?)

Direct questions tend to bring direct answers (eg. "how good are you technically?")

Asking a candidate to handle a hypothetical problem-solving situation can be enlightening.

Asking a candidate to ask you questions about you, the company, the job. Their questions will tell you a lot.

Retaining employees who want to quit

When an employee says they want to quit, its almost always becomes he feels he is not important to you.

Thus when they first bring it up, if you do not deal with the situation right at the first mention, you'll confirm their feelings and the outcome is inevitable. Drop what you are doing, sit them down and ask why they're quitting. Let them talk–don't argue about anything. They've rehearsed their speech countless times. After they've finished going through their reasons for wanting to leave, ask more questions. Make them talk, because after the prepared points are delivered, the real issues may come out.

Just keep listening, you can't win the war–but you can lose it.

You have to convey by what you do that they are imprint to you, and to find out what is really troubling them. Don't try to change their mind. After they've said all that they have to say, ask for whatever time you need to prepare yourself for the next round.

Then go back to the subordinate with a solution–one that addresses his real reasons.

If he says that he's only getting this offer because of blackmail, respond "You did not blackmail us into doing anything we shouldn't have done anyway. When you almost quit, you shook us up and made us aware of the error of our ways. We are just doing what we should have done without any of this happening."

If he says he's accepted a job somewhere else and can't back out, tell him that he's really made two commitments: first to a potential employer he only vaguely knows, and second to you, his present employer. and commitments he has made to the people he has been working with daily are far stronger than one made to a casual new acquaintance.

Compensation

Money can serve as two different types of motivators depending on the person:

- If the absolute sum of a raise in salary an individual receives is important, he is working within the physiological or safety modes.

- If what matters to him is how his raise stacks up against what other people got, he is motivated by esteem/recognition or self-actualization, because in this case money is a measure of achievement.

For managers, the percent of their salary which consists of a performance bonus should rise with their salary (from 5-10% to 50%).

Salaries can be based off of experience or merit, or a combination of both.

Experience-based salaries create fairness but don't incentivize performance. Merit-based salaries can create a contentious competitive environment.